Tell Your Friends To Watch The Book Trailer.

“The Idiot and the Odyssey: Walking the Mediterranean” took readers on a 4,401-kilometer MedTrek through Morocco, Spain, France, Monaco and down to the Italian coast to Rome

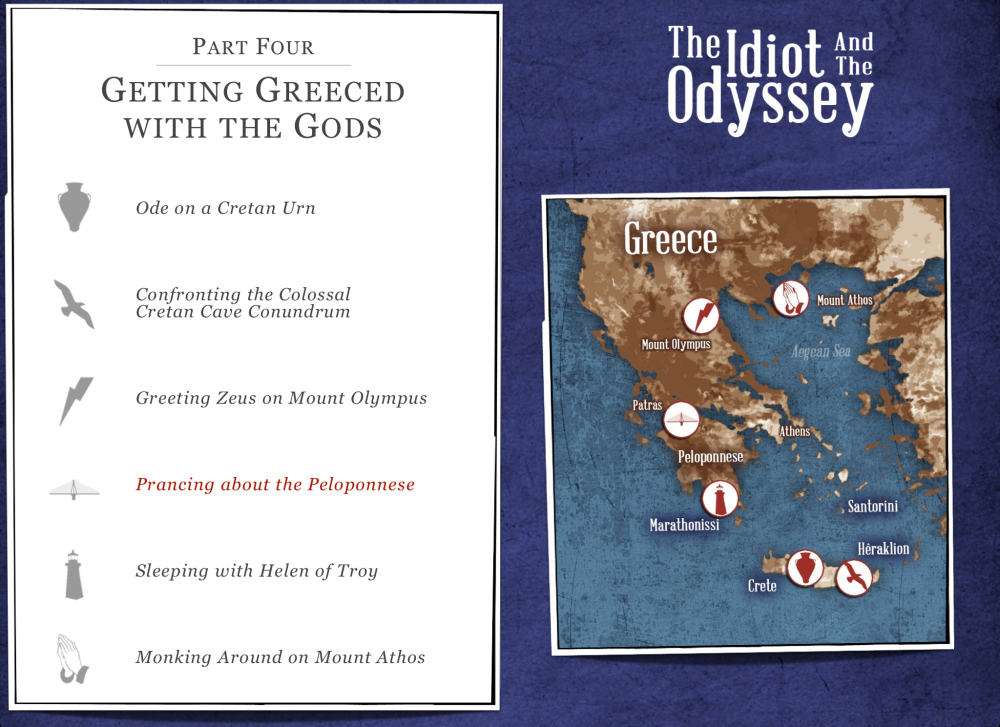

“The Idiot and the Odyssey II: Myth, Madness and Magic on the Mediterranean” takes readers 4,401-kilometers from Rome to the boot of Italy, around the islands of Sicily and Crete, into the Peloponnese, up Mount Olympus, on to numerous Mediterranean islands and down the Turkish coast to Imzir.

“‘Crete,’ I murmured. ‘Crete…’ and my heart beat fast.” – Zorba the Greek, Nikos Kazantzakis

View Larger Map

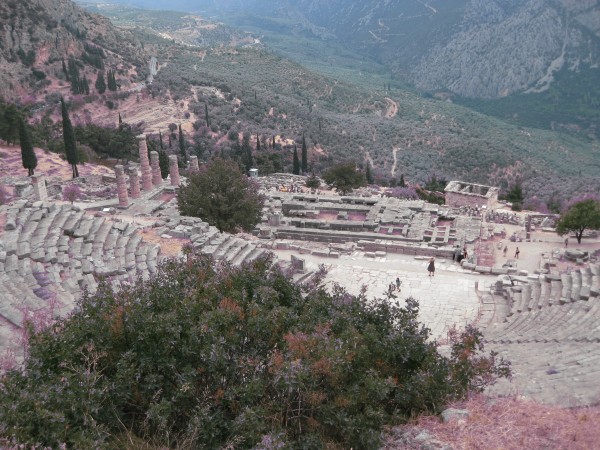

I didn’t decide by myself to head to Crete, Greece’s largest island in the southern Aegean, to MedTrek for two months. First I went to pay tribute to, and get some guidance from, the iconic Oracle at Delphi. Circe told me the renowned seer would inform me how to approach the Peloponnese and circumnavigate Europe’s southernmost isle of Crete.

Circe’s seventh labor embodies the physical and spiritual direction that she suggested I obtain from time to time. “Visit the Oracle of Delphi – who ‘knew what was, what had been, what would be’ – and let her lead you to the cave of Zeus’ birth, the world’s greatest travel writer, and the end of an historic footrace in Sparta.” Not everyone likes the advice that they get from soothsayers like the Delphic Oracle: “You visionary of hell, never have I had fair play in your forecasts,” Agamémnon complained in The Iliad when he was displeased with another clairvoyant’s prediction – but I plan to listen and obey.

I stop in the picturesque village of Arachova, perched on the flank of Mount Parnonas, the home of Apollo and the nine Muses, on my way to consult the Oracle. When I reach Delphi, I’m flabbergasted that some ornate hand-carved walking sticks in a shop cost €60, but not surprised to see hotels named Apollo, Oracle, Zeus, Kouros, and Sybilla near restaurants called Dionysus and Vesuvio.

I start my outing in Delphi, which is seven kilometers from the Mediterranean as the birds fly, carefully carrying a €4.50 glass of fresh orange juice as I stroll through the Sanctuary of Athêna Pronaia just after sunrise. Pilgrims traditionally pay a visit here before seeking advice from the eminent Oracle, who speaks the will of the Apollo.

I promised Athêna and Apollo, the god of prophecy and healing, that I would learn both ancient and modern Greek before my arrival in Delphi. That didn’t quite work out, so I practice my multilingual introductory spiel in Athêna’s sanctuary before I humbly stroll up Delphi’s Sacred Way to the Temple of Apollo, located at the exact spot that Zeus and his gang considered the center of their flat earth.

As I approach, I formulate questions posed by 27 well-meaning friends who want a response from the Oracle, who’s also been known in the fortune-telling biz during the last few millennia as the Pythia or the Delphic Sibyl. Their questions are mostly about personal or political issues. Would a female pal fall in love, or even make love as, Odysseus said, “men and women by their nature do,” anytime soon? Would Greece resolve its debt problem? Would Sarah Palin (this one from my right-wing mother) ever win the presidency? Would China get out of Tibet?

Tell The World That The Idiot & The Odyssey Is The Coolest E-Book Ever Written.

I’m not sure that the Oracle, who is shrouded by vapors and slightly resembles Vanessa Redgrave in her early 60s, even has a clue about current affairs, romantic or otherwise. However, I told my inquiring pals that I’d try to get them some answers before dealing with my own logistical conundrum.

It turns out, according to a priest who “translates” messages conveyed by the Oracle’s trance-induced utterances and paroxysms, that Pythia/Sibyl doesn’t really make predictions about love, elections, or football games. Instead she prefers to simply give advice, either coherently clear or irritatingly ambiguous, from atop a rock where she’s been holding court since her inner sanctum in Apollo’s sanctuary was destroyed by an earthquake centuries ago. The priest warns me, and every other visitor, that taking photos of the Oracle will produce very bad omens. In fact, there’s not a single representation of her, in stone or bronze or paint or photo, in the worth-visiting museum nearby.

I’m hardly the first to seek out the Oracle’s guidance. According to Strabo, ten percent of the men from the Greek city of Chalcis, which was in the midst of a serious drought, came to offer themselves as a sacrifice in 730 BC in an effort to reduce the population. Instead, the Oracle sent them to found the colony of Rhegion, which means “break away,” that we know today as Reggio Calabria on the toe of Italy. Pretty sensible resolution, I think.

At first, all I can mutter during my séance with the world’s most reputed psychic is “Good Morning” and “Thanks for seeing me!” in Greek and six other languages. The Oracle doesn’t seem at all bothered by my lack of decent Greek. She also dismisses my questions about Tibet and romance and doesn’t waste more than a minute considering my primary query.

“The Idiot might personally prefer to proceed to the nearby Peloponnese Peninsula and calmly walk counterclockwise towards Athens until his appointment to climb Mount Olympus and visit the monks at Holy Mount Athos,” she informs me with slightly somber seriousness. “But before that The Idiot should visit the birthplace of the father of all gods in the caves of Crete.”

One reason she directs me first to Crete is because the buzz, from authorities like Hesiod and Homer, is that Zeus was born on the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean (after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and Corsica), which was also the birthplace of Minoan culture and home to Europe’s first real civilization. I haven’t been to Crete since 1982 and look forward to again visiting the Palace of Knossos and discovering the cave where Zeus was born.

My next question for the Oracle, who is far too intimidating to invite out for a bonding chai, is if I should quit MedTrekking and get a day job.

“Should you give up your MedTrek?” she chuckles. “That’s like asking whether I should stop being an oracle. Our mid-life projects stimulate, intrigue, and define us. We should both keep at them while we’re physically, emotionally, and spiritually able to. Illness or death will let you know when it’s time to stop, though I’m here for eternity.”

Then, as suggested in the book Twenty-Four Hours a Day, I tell her that this morning I “pray that I may not ask to see the distant scene. I pray that one step may be enough for me.”

After our chat, I have a vigorous four-hour romp around the Oracle’s hillside home before meandering through the museum adjacent to the luxuriant archeological site. There I admire a stone frieze of the gods, which originally decorated a building in the area, which was sculpted around the same time that Homer wrote The Iliad. I am also transfixed by the bronze statue of the proud and erect Charioteer of Delphi.

This may sound vainglorious, but I may be the only visitor who realizes that I have something very much in common with the Charioteer, a life-size relic cast around in 478 BC and taken to the 474 BC Olympic Games to commemorate a victory.

What is it? The noble appearance? The victor’s headband? The colored eyes?

Nope. Feet.

My feet, after walking more than 7,000 kilometers around the Mediterranean Sea, look exactly like the Charioteer’s.

The Charioteer’s feet.

The Idiot’s feet.

A good friend, Gayle Guest, compares our feet when she sees a photo of the Charioteer and suggests a surprising premise: “I think your feet represent Homer’s books. Your left foot is The Iliad and depicts your journey to Troy and your right foot represents the journey home and spiritual growth in The Odyssey. The ten toes symbolize both the ten-year war and the ten-year journey home.”

I get a last snapshot of Oracleville before heading downhill to Patras to catch a ferry to Crete. As I leave, I feel that the Oracle embodies a conclusion arrived at by Lao Tsu: “Those who know do not talk. Those who talk do not know.”

Zorba the Greek author Nikos Kazantzakis best defined the more-than-mere-physical beauty of Crete’s landscape when he called it a palimpsest, a lovely word often defined as “rewritten manuscript.” This was due, Kazantzakis said, to the fact that the land, like a parchment that has been scraped clean and used again, bore “twelve successive historical inscriptions: contemporary; the period of 1821; the Turkish yoke; the Frankish sway; the Byzantine; the Romans; the Hellenistic epoch; the Classic; the Dorian middle ages; the Mycenaean; the Aegean; and the Stone Age.”

I don’t need an Oracle to make my first move in Hêraklion, which is named after Hêraklês and became the capital of Crete in 1971. Hêraklês arrived here, on one of his own twelve labors, to deal with the Cretan bull that was ravaging the land. My eighth task, to “meet with Zeus, the master of cloud, at the cave of his birth on Crete,” is less challenging than that.

When the rain stops at 8:30 a.m., I decide to head west around the island to the village of Fodele, the birthplace of the Spanish Renaissance artist El Greco in 1541. Then I continue towards the seaside villages of Bali (I’ve visited the other Bali, in Indonesia, and thought this might have a similar allure), Rethymno, and Chania, the animated crescent-shaped port below the snow-covered peak of Lefká Óri, or the White Mountains.

Why kick off my MedTrek around Crete by heading counterclockwise, which seems to be my MO, for over 600 kilometers rather than go the other way?

I plan to meet Walter Lassally, the Academy Award-winning director of photography on Zorba the Greek, near Chania. I also want to simply MedTrek for a couple of weeks before ardently pursuing Zeus, and this directional choice will give me a chance to hike the fabled Samariá Gorge before the tourist season officially begins. And I don’t have an appointment to see Canadian archeologist Sandy MacGillivray in Palaikastro at the eastern tip of the island until mid-May.

My first day on the Cretan path starts at the Dominican Monastery of Ayios Petros near the Hêraklion port and ends thirty kilometers away at Fodele Beach, just a few kilometers from El Greco’s birthplace.

In between, I have a stupendous cloud-shrouded view of Zeus’ supposed profile lying quietly under Mount Gioúhtas, where some Cretans believe he’s entombed; learn that the seacoast is rocky, steep, pathless, and wild (Michelin Green Guide writers were obviously on drugs when they wrote that “there is a marked route around the island”); confirm that the goat/sheep population hasn’t been impacted by Greece’s economic woes; and am soaked from hair to toenail by mid-April rain.

Zeus’ purported mountain tomb, incidentally, led to a negative rumor about the people of Crete. Callimachus, the third-century BC poet and scholar, wrote in his Hymn to Zeus that “Cretans always lie” because they constructed a tomb for Zeus who is immortal. An immortal, Callimachus pointed out, doesn’t need a tomb.

Before leaving Hêraklion, I see one of Crete’s famously large eagles and the massive bird evokes another line that Kazantzakis wrote in Zorba: “How beautiful Crete is…Ah! If only I were an eagle, to admire the whole of Crete from an airy height…”

Eagles are one of the many birds that deliver good and bad omens throughout Homer’s epics, which are speckled with sentences like “And Zeus that instant launched above the field the most portentous of all birds, an eagle, pinning in his talons a tender fawn.” That particular eagle took the fawn to the altar of Zeus in Troy and, as a result, the Greeks “flung themselves again upon the Trojans with joy renewed in battle.”

Indeed, “joy of action,” rather than the “clammy dread,” is what inspired Greek troops during that war. Homer wrote that “an eagle beating upward, in its claws a huge snake, red as blood, live and jerking” was an ill-fated portent for the Trojan troops when “the snake fell in the mass of troops.”

Some Trojans didn’t pay eagles much heed.

“You would have me put my faith in birds, whose spreading wings I neither track nor care for, whether to the right hand sunward they fly or to the left hand, westward into darkness?” Hektor said at Troy. “No, I say, rely on the will of Zeus who rules all mortals and immortals. One and only one portent is best: defend our fatherland.”

I recall, looking at the eagle, another line from my 365 Tao Daily Meditations: “When birds fly too high, they sing out of tune.”

Bali and Crete

My counterclockwise choice doesn’t mean I’m not equally excited about running into Zeus and his cavernous birthplace(s); visiting Knossos and King Minos’ labyrinth (the story of the Minotaur and the labyrinth is one of my favorites); and climbing Mount Ida and discovering other remnants of Minoan civilization. I’m fairly sure these natural and man-made treasures on Crete aren’t going anywhere.

Don’t get the idea that the coast between Fodele Beach and Bali (pronounced Baa-LEE) is sandy. My first twenty kilometers are rough, rugged, steep and slippery. I MedTrek on the seaside, on country roads through villages like Sises (Note to self: bakeries in little towns like Sises tend to run out of bread before noon), and on the national road when it’s the only option (Warning to self: Cretan drivers treat the shoulder of the road, which is the only place to walk, as the middle of the road).

The seacoast near Agia Pelagia.

The seaside terrain often “forces” me onto springing-to-life hillsides and into fruit-rich fields and orchards, where I encounter omnipresent Greek Orthodox chapels of various sizes and refuel with oranges that I pluck off trees.

I also discover some novel, to me anyway, agricultural advances that might date from the ancient Minoan culture that thrived on Crete during the Bronze Age that began in the 27th century BC. How, you might wonder, do the Cretans keep tree limbs growing correctly when they’re battered by the many different types of vicious Mediterranean winds? What’s the real reason that goats stay in their pens on Crete? The pictures tell the story.

Crete’s Bali features a few small, sandy beaches, but no one, except an Idiot, would expect it to resemble its Indonesian counterpart. Still, it’s a gem on the northern coast and looks alluring as I approach.

I send my SPOT tracking position from the Bali port while I explain my MedTrek project to Georges, the owner of the Akrogialli Taverna who says he saw me walking near Hêraklion earlier in the day. He’s so impressed that I hoofed it all the way here that he plies me with free coffees to keep me going.

During our wide-ranging conversation, after I explain my fascination with Odysseus’ homeward journey, Georges reminds me that Cretan warrior Idomeneus and his followers not only escaped death in Troy but also made it expeditiously home after the Trojan War. Who knew?

Rain keeps me in Hêraklion the next day so I decide to knock about Knossos and mingle with King Minos, one of Zeus’ sons, before continuing west. I also visit the morning market on Odós 1866 to pick up some yoghurt, honey, and figs and laze about the Platía Eleftherías, Liberty Square, and the Platía Venizélou to do some afternoon people watching. Then at sunset, which can be witnessed from the terrace of my sixth-floor room above the port, I walk out to the Venetian Fortress at the entrance to the harbor.

I learn something new each time I visit Knossos, which Homer called “the chief city of King Minos, whom great Zeus took into his confidence every nine years” and other Minoan palaces at Phaistos, Mália, and Zakros. For example, I didn’t know that during the Trojan War the “Kretans, all who came from Knossos…all from that island of a hundred cities served under Idomeneus, the great spearman.”

“Follow the weathered Royal Road,” I sing to myself as I approach the grounds of Knossos, which was initially explored by Sir Arthur Evans in 1894. There’s no shortage of history here. Homer refers to Knossos in The Iliad when he describes the finely crafted shield that Hêphaistos made for Achilles, “in which the famed lame-one wrought a chorós like the one that Daedalus fashioned for Ariadne of the beautiful tresses in broad Knossos.”

After calmly strolling up the weathered cobblestones of the Royal Road into Knossos, I pick up other delicious tidbits while I traipse around the ancient site and not-so-sacred grounds of what was once the greatest city in the Mediterranean. That’s really no surprise because this spot was home to Neolithic man long before the first palace appeared around 2000 BC, before the era of King Minos began in 1700 BC. Today I discover the origin of the word “Wow,” investigate the world’s first urban garbage dump and compost heap, and tell a French tour group that the frescoes at Knossos are reproductions.

The word WOW came from the still-standing differently colored pithoi that held Water, Oil and Wine.

My imagination is stimulated by envisioning the labyrinth that Daedalus designed here to hold the Minotaur, the monster with a bull’s head and a man’s body to whom King Minos fed his enemies. Knossos is also where Theseus seduced Minos’ daughter Ariadne and was able to find his way out of the labyrinth after slaying the Minotaur when Ariadne gave him a mitos, or ball of thread, that he unwound to guide himself. I’ve always enjoyed the definition of mitos as a lifeline created by the Fates at birth that we each unravel as we age to avoid being forever lost in the labyrinth of life.

Sandy MacGillivray, an archeologist whom you’ll meet when we explore his dig in eastern Crete, is among many who still have a lot of questions about Knossos.

“The hard truth is that well over one century after Sir Arthur Evans declared that he had found the Palace of Minos at Knossos, we still do not know what he really found,” says Sandy, who wrote a book called Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archeology of the Minoan Myth. “There is still no direct evidence of the existence of a monarchy, let alone a legendary King Minos or the Daedalian Labyrinth where Theseus slew the Minotaur. Why have we not found any evidence of royal burials? Why is Minoan art void of political propaganda?

“I don’t disparage Sir Arthur Evans in my book, but rather I criticize the discipline of archeology,” Sandy explains as we discuss various academic interpretations of Knossos from Strabo through Victor Bérard. “Academics never agree and that’s one of the reasons there’s seemingly so little progress. Socrates thought King Minos existed but minos is often the translation of ‘first king’ or ‘man’ rather than a particular individual. I tend to think of Knossos and other Minoan palaces as elaborate festival halls, great sanctuaries, and lively places where the community gathered to celebrate on their many festival days.”

I pick up more novel information about the site during a visit to the Archaeological Museum in downtown Hêraklion.

I learn that the Minoans’ domestic produce included cattle, sheep, pigs, and goats and that they cultivated wheat, barley, chickpeas, grapes, figs, olives, and poppies. I discover that the snake goddess was a sovereign figure in the Minoan pantheon and that snakes are symbols of fertility. I agree with Sir Arthur Evans that La Parisienne (he named it that because of the “malicious charm of her expression”) is the sexiest fresco found during the New Palace period.

Although I don’t make much progress trying to decipher the symbols inscribed on the Phaistos Disk, I marvel at a marble statue of Zeus Serapis depicted as the Lord of the Underworld with the three-headed hound Cerberus at his side. And I can see why warriors at Troy felt so protected wearing a boar’s tusk helmet.

Zeus hanging with Cerberus in Hêraklion

A boar’s tusk helmet

My imagination goes wild when I look at cups and bowls from the palatial buildings that, I figure, indicate heavy-duty partying, and coins that show the Minotaur on one side and a labyrinthine swastika with a star or sun motif on the other.

The sign I receive from an ode on a Cretan urn is particularly apropos for my walk. It reads simply “With each step, a breeze will rise.” As I enjoy the message that seemingly endorses my perambulations, I recall that Thich Nhat Hanh once told me “the breeze is the peace and joy that blow away the heart of sorrow.”

How was I able to so astutely gather all this information in just a few hours? Because I was wearing the comme il faut faux military pants that are the de rigueur mode for Greek men, which enabled me to mingle with King Minos and Zeus without looking like another tourist.

The terrain beyond the hill behind Bali is comparatively flat. I proceed along the rocky, scrubby, and sandy sheep-and-goat populated coast with constant views of a snow-capped peak. I walk through villages like Panamos, along the beach, through sheep-grazing fields and into a few massive resort hotels. At the still-empty Creta Panorama Hotel, a circular labyrinth walk takes me through luscious and well-tended grounds. I see a few people get in the water for the first plunge of spring and can’t believe there will ever be enough tourists to empty the rent-a-car agencies of their inventory, especially when the price of gas exceeds $10 a gallon. Yet despite my skepticism every house seems to rent cars on the side.

It’s a 31-kilometer MedTrekking day into Rethymno, and I’m invited to join a big Greek Easter dinner at the Rethymno Beach complex. Instead I choose to relax at sunset on a chaise longue on the beach with a homemade dinner – cheese, two Easter eggs, two rolls, a banana, and an orange. I’m impressed that there are another two chocolate Easter eggs on my pillow when I bed down in a modestly priced hotel.

Easter becomes a bit more exciting for me the next night, when I’m asked by the hotel concierge to present photographs of my 60-kilometer Easter parade walk between Skepasti and Georgioupolis to a group of touring Greeks in their 80s.

Who could say no?

Not me. And I use the occasion to personally select winning and losing photos in a variety of controversial categories:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Loser: Beaches, ready for the summer season to kickoff, are prepared to welcome sunbathers from dawn to dusk. But despite sunshine locals stay away from the sea due to still-chilly weather.

Winner: Cafés are crowded throughout the afternoon.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Loser: There is a lot of pressure from the church to swing the vote in favor of this delightful coastal chapel in Rethymno.

Winner: You have to walk on water to get to this almost inaccessible chapel in the sea in Georgioupolis.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Loser: The Photographs Are Forbidden sign mounted on barbed wire at a seaside military base.

Winner: The multiple recycling containers on a beach in Rethymno.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Loser: This hard-to-describe gigantic match and human cannon contraption.

Winner: This artfully constructed warrior with a bow.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

The Idiot awarded a two-way tie for first place.

Winner: This view of a snow-capped mountain.

Winner: This view of the port in Rethymno.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Winner: This lovely path enabled the parade to stay near the sea.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Losers: Crete’s lambs took a big hit and were found roasting on spits in homes,

hotels, tavernas, and beaches on Easter weekend.

Winners: These perky, pesky and pleasant goats on a cliff above the

Mediterranean were among the luckiest beasts on Crete on Easter weekend. They lived.

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

The Idiot managed to catch a couple of rare beach bums in a shot that illustrates that the

weekend’s comparatively flat Easter Parade terrain will be replaced by mountains tomorrow.

Like This And We Will Think You Are The Coolest Fan In The World.

I also photographed a lot of random sights on my Easter weekend walk. These included Sri Lankans playing Easter cricket, a patch of my own private Astroturf for sunbathing and lots of Greek beach barbecues with ladies dancing. And I learn that one reason the buses run so efficiently is because their biggest advertisers are ferry companies, like Minoan Lines and Anek, who pride themselves on maintaining a strict schedule.

I wisely avoid Highway 90, the dangerous seaside national road, on Easter Monday by crossing the river in Georgioupolis and heading straight up the mountain on little-traveled two-lane blacktop.

My first treat is a very crowded church service – with chanting, singing, praying, and merry-making by an overflow crowd – at a small hillside chapel in Argyromouri. The rest of the day is a mindless, meditative and sometimes uphill, meander through little towns like Vamos, where I have a Greek coffee at a café with some British habitués who live there, until I reach the sea at Kelyves, where I have six pieces of honeyed baklava for lunch. Kelyves is a somewhat downtrodden seaside resort, but that may be explained by the lack of a real beach and waves that thrash against a manmade breakwater.

I continue on the seaside Old Road through Kalima until I arrive in Souda, which is where ferries from Piraeus to Chania dock. There’s a bus line to and from Chania, which is only six kilometers away as the cars drive, but much further for a MedTrekker who hikes across the sparse Akrotiri Peninsula, where two monasteries and numerous archeological treasures can be found. My walkabout on the arid, windswept, vacant, and vast peninsula takes me through lots of little villages, all of which seem to start with K or C, like Kalathas, Kalorrouma, Koumares and Chorafakia.

Lunching With Walter the Greek

The highpoint of the day is a Mediterranean seaside lunch with Zorba the Greek Academy Award-winner Walter Lassally in the village of Stavros, where the film was shot half a century ago. I immediately baptize the 84-year-old, Berlin-born, British-raised cinematographer Walter the Greek because I realize that he’s a contemporary symbol of the independence, passion, spirit, and wile embodied by Anthony Quinn’s portrayal of Zorba.

Lassally, who “retired” to the seaside village in the 1990s, loves the place so much that he bequeathed his Oscar to Christiana’s Restaurant. The much-handled statuette was on permanent display on the bar for years until it was destroyed in a fire at the restaurant in 2012.

Comparatively sleepy Stavros has been spared the onslaught of tourist resorts, large hotels, and supermarkets. There is one public telephone, and Lassally frequently has lunch at either Christiana’s or Maleka’s Taverna.

“When we shot Zorba there were no roads, no electricity, no water, and no trees — and not too much has changed,” Lassally says while drinking a glass of honeyed retsina on the sandy beach at Maleka’s. “I’ve been around the world and never found a place to live that’s better than this spot on Crete. It’s easy, relaxed, and I like the volatile attitude of the mountain people.”

As director of photography, who shot a dozen films in Greece and scores of others throughout the world, Lassally was best known for his work on Tom Jones before tackling Zorba. Today, perhaps subconsciously influenced by the verve and vitality of both movies, he’s living life to the fullest and seems to embody Zorba’s assertion that “a man needs a little madness, or else he never dares cut the rope and be free.”

In his mid-80s, the multilingual Lassally (he speaks German, English, Greek, and French) is learning Polish, his mother’s native tongue; is preparing to shoot a documentary about the 1866 Cretan revolution; is organizing a pan-Balkan film festival; and takes his two dogs on daily walks. During lunch, our conversation ranges from his thoughts about the director’s cut of Heat and Dust, the not-for-the-good changes in the Hollywood system, the ongoing collapse of the Greek economy, and the jealous nature of Greek women when it comes to Zorba’s philosophy that “me – I live as though I might die tomorrow.”

“Nobody around here thinks he’s Zorba the Greek,” Lassally insists as we walk on the beach where he filmed the hilarious hillside logging accident and Zorba’s dance, which is called the sirtaki and is an iconic cliché of a Greek night out. “But we’re all fascinated by his story.”

Lassally describes some of the social restrictions in Stavros (“I can never have a conversation with two women at once around here because they all detest each other”) and his fascination with the I Ching.

“I wrote a book called Thirty Years With the I Ching, but I couldn’t get a publisher, so now it’s called Forty Years With The I Ching,” he jokes before he describes the bitter enmity that has existed for generations among some of the larger families in the area. “The Cretans are very tough and usually have rows over land, but once there was a murder here over deck chairs on the beach.”

He thinks that a long-lasting feud may have been responsible for the torching of Christiana’s, though he is philosophic about the tragedy.

“The fire was almost certainly started deliberately, probably as a result of one of those tribal fights that unfortunately are only too common here, and I look upon it as the end of an epoch,” Walter says. “The Oscar had a good life. There are thousands of photos of it with me and with the mountain that the film made famous.”

As I leave Stavros and Walter behind, I recall another line from Zorba the Greek: “On this Cretan coast I was experiencing happiness and knew I was happy.”

A Whole Lot of Kissing Going On

The buzzing and busy port of Chania with its Venetian harbor, iconic lighthouse, and crescent-shaped seaside promenade is one of the most pleasantly active social spots on the Mediterranean. But due to an impending storm it has a dark, foreboding, and mystical appearance when I hit town after the lunch in Stavros.

Chania has been completely revamped since its Ottoman and Venetian days and manages, from my perspective, to out-Saint-Tropez Saint-Tropez. There are dozens of portside restaurants with barkers beckoning passersby and chic jewelry stores along an immaculate port, so clean it could be mistaken for a Disneyland attraction.

Why do I get an early evening haircut in Chania after my day with Walter? I’m preparing myself for an anticipated onslaught of some serious snogging in Kissamos, a town down the road with a name that overwhelms me with romantic fantasies because they are going to call it Kissalot for a day. The barber, who says he’s a former chess champion of Greece, is so involved in a computer chess game that he gruffly says, “Sit down” and gives me the most unpleasant welcome I’ve ever had in a barber shop.

“I can’t be human and play chess at the same time,” he half apologizes. “The shop’s not supposed to be open tonight (it’s 7:00 p.m. on a Wednesday), but I was too engrossed to close the door.”

He doesn’t have a clue what I’m talking about when I mention the possible orgy in Kissalot.

I check into the €30-a-night Ideon Hotel just outside the city walls and start my next MedTrekking day on a flat seaside with lots of packed sand, lots of urban streets (with scores of mini-markets, cafes and tourist shops), a former WWII German military base, and a few luxury hotels.

I amble through a half dozen little seaside villages – Stalos, Agia Marina, Platanias, and Gerani – that all feature a resort-and-beach-waiting-for-the-season-to-arrive wistfulness. The style of hotels and lodgings ranges from the fairly spectacular for individual high-end travelers, to the spectacularly downtrodden for low-end package tours. I have a conversation with a lovely Danish girl – she actually quotes a line from The Iliad claiming that she is “a traveler like yourself, well-made, well-spoken, clearheaded, too” – at one hotel and buy some excellent olive bread at a bakery.

But the skies open – and don’t close – around 2:00 p.m. and I wind up soaked and well short of my intended destination of Kissamos. The Zeus-is-pissed outbursts and downpours force even an otherwise self-sufficient MedTrekker to frequently run for cover during the intermittent deluges. It’s any port in a storm when the god of thunder unleashes a fury of striking lightning, cracking thunder and driving rain.

Though my quick-dry gear is already soaked, numerous people help me get out of the rain. A Romanian gardener lets me into his shed, the English receptionist at the singles-only Hotel Mistral in Maleme (www.singlesincrete.com) offers me shelter from the storm, I climb into an old pillbox in a bunker at a former World War II German air base, and the monks give me cover at a Greek Orthodox monastery.

When the sun returns the next morning, I leave the Gonia Monastery and spend a glorious day traversing the Rodopos Peninsula between the villages of Kolymbari, where they’re building a gigantic hotel, and Kissamos amid nearly vertical hillside olive groves, well-balanced grazing goats, nectar-seeking buzzing bees, and exhilarating views of the multicolored (brown from the rain, grey from the clouds, blue in spots) sea. Kissamos is temporarily changing its name to Kissalot in honor of a royal wedding in London and, according to local buzz, will become the kissing capital of the world for a day.

Along the way I meet a Canadian couple (she’s of Greek heritage) who have come to baptize their young, blond-haired son. “Holy Moly,” she says when she learns how far I’ve walked. I tell her about Circe and the origin of the “Holy Moly” expression, and she explains that “the baptism will be a big shebang, but no one can understand how/why my Greek son has such blond curly hair.”

When I return to the beach I’m taunted by some joy riders in a red truck. I probably don’t help my cause when I pretend to be a matador as they try to run me down. As I near Kissalot I put on orange hiking shorts and a bright blue shirt for the occasion. In retrospect, I fantasized too much about the possibilities and potential of arriving in the kissing capital of the world.

I enter Kissamos (amos, as in Kissamos, means “thick sand”) late in the afternoon expecting to have scantily clad, lithe Greek maidens throw rose petals in my path and smother me with kisses. But an arrogant 12-year-old Cretan kid on a moped informs me that the snogging stopped the second the wedding ended in London. I am hours late and to my dismay, and that of my romantic imagination, there’s no kissing at all and I don’t see a single lithe Greek maiden.

“You should have been here at noon!” the kid chortles.

I rush to the Kissalot city hall and appeal to the mayor, who looks all puckered out, but am abruptly (a bit too abruptly, I thought) told that Kissalot is finished. I’m back in good old Kissamos.

“You should have been here at noon!” the mayor guffawed.

I’m so distraught at my bad timing that I walk to the end of the beach, reflect on the many injustices in the world and decide I need a break from rain-provoking Zeus and temporary Kissalot.

Gorging on a Gorgeous Gorge

I take a day off and do nothing except enjoy an overflowing mixed-grill, mixed-seafood combo that I have the chef concoct at the Monastiri Taverna in a Venetian building on the port in Chania. It’s just the right meal after almost 300 kilometers of Cretan MedTrekking and afterwards I relax for an hour at my table on the waterside terrace, observing people promenade. At the end of a day off, there’s nothing sweeter than watching dusk turn to dark on a fine port like this one. The air, the smell, the lights, the strollers, and young couples add a warm and fuzzy feeling to an array of other Mediterranean sentiments.

The next morning I check out gorge-ous Crete and hike down and through the Samariá Gorge – the island’s most famous, most touristic, most iconic and most must-see natural site. It’s the first day the trail has opened this spring and I’m among the first on the path.

Do you want some comparatively easy MedTrekking amid the usually savage landscape and rocky Mediterranean seaside in southwestern Crete’s White Mountains? Then walk the island’s equivalent of the Grand Canyon and follow the blazed E4 hiking trail north or south along the coast.

The 1,250-meter (4,100-foot) descent through the Samariá Gorge is 13 kilometers long, but it’s a downhill walk in the (national) park and an exceptional deal for the €5 entrance fee. There’s a constant supply of spring water, WCs, trashcans, picnic tables, shaded rest areas, some wooden steps, and park rangers.

There are, however, signs warning hikers to “Walk Quickly” to avoid falling rocks, steel netting to protect hikers from falling rocks, and a chapel en route if all else fails. The path through pine and plane trees is generally in excellent shape, though some hikers have trouble crossing the wood-slatted bridges on the river running between sheer rock walls that rise to over 2,000 meters. There’s one very cool passage through the walls that’s only about ten feet wide and I make the walk from Xilóskalo on the Omalós Plateau, at 1,050 meters, to Agia Rouméli on the edge of the Libyan Sea in under four hours.

Most gorge-goers take a late afternoon ferry back to Sfakiá, and civilization, when they reach the sea. But I am so smitten by the well-marked E4 yellow-and-black marked hiking path, a MedTrekker’s dream, that I hike it for three days. It follows the contours of the coast, is well marked, passes beaches and chapels, and certainly makes it unnecessary, as the Green Michelin suggests, to take a boat trip to see the mountainous coastline. As I walk I recall another paragraph in Zorba the Greek, which, before it became the celebrated film, was a novel by a Greek author and philosopher Nikos Kazantzakis:

“I climbed a hill and looked around. An austere countryside of granite and very hard limestone. Dark carob and silvery olive trees, figs and vines. In the sheltered hollows, orange groves, lemon trees and medlar plants; near the shore, kitchen gardens. To the south, an expanse of sea, still angry and roaring as it came rushing from Africa to bite into the coast of Crete. Nearby a low, sandy islet flushing rosy pink under the first rays of the sun.”

I head west to visit Elafonissos (it’s considered a two-star attraction by the Michelin Green Guide because the peninsula features pink sand, rolling caramel-colored dunes, and clear turquoise-tinted water), Paleochora and Sougia. Then I return and go east towards Loutro, which is accessible by foot or ferry, and Sfakiá.

Loutro – where there are sheep and chicken being barbecued on every smoky and smelly grill – is so rarely visited by tourists that I find a room for €10, an internet/satellite connection with a parrot guarding the Wi-Fi, and meet almost everyone in town within an hour.

“I love docking each night in a place I can only get to by boat,” the ferry captain says about the place he’s chosen to live when we meet in a bar.

The next morning a café owner offers me a hardy Greek coffee at 6:30, an hour before his usual opening time. He refuses to let me pay, and I lamely leave a pile of coins on the table.

Although I only meet a few other people on the E4, there’s no shortage of goats (I still get a kick out of every goat I talk to), and when I arrive in Sfakiá I’m pleased to encounter Despina Fountulaki at her Café Dispensa. She makes me a stiff filter coffee with a dash of milk (again free, again I tip) and takes my picture because, she says, “you look so sexy and gorge-ous for someone who’s walked so far.”

Follow

Follow