I’d been thinking about my friend Joel Stratte-McClure ever since I heard that some swimming events of the Paris Olympics will be held in the Seine.

A river that, right now, contains “alarming levels of bacteriological pollution,” a nonprofit foundation said last week, based on six months of regular sampling. Other studies also have raised concerns about whether the Seine will be safe for swimming and a 2023 trial event was canceledbecause of pollution.

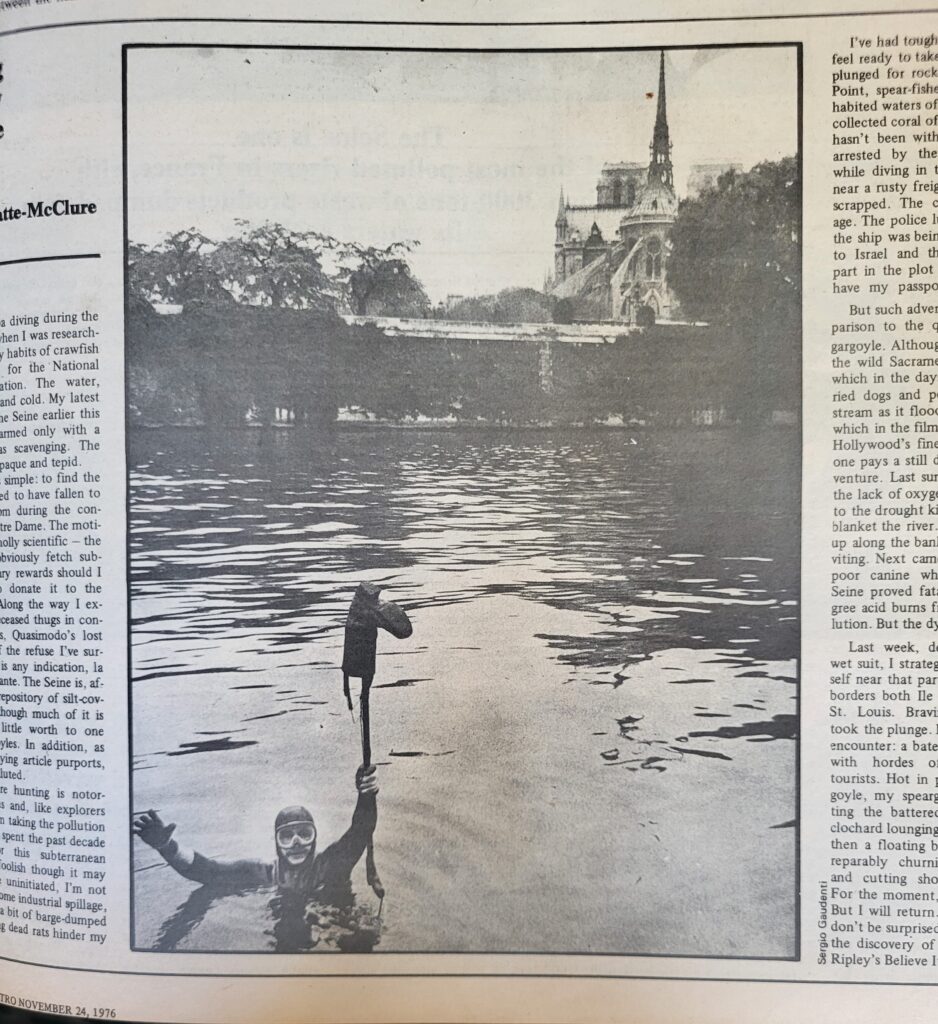

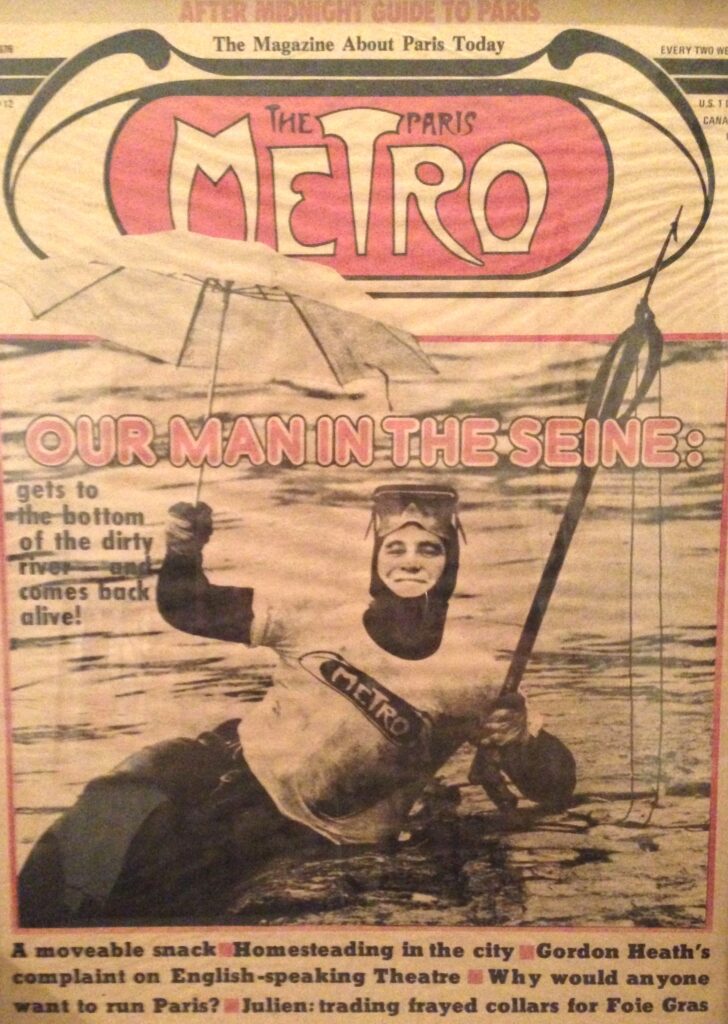

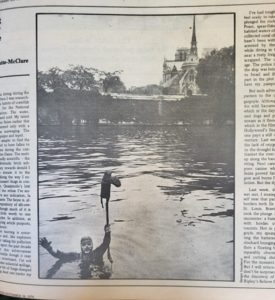

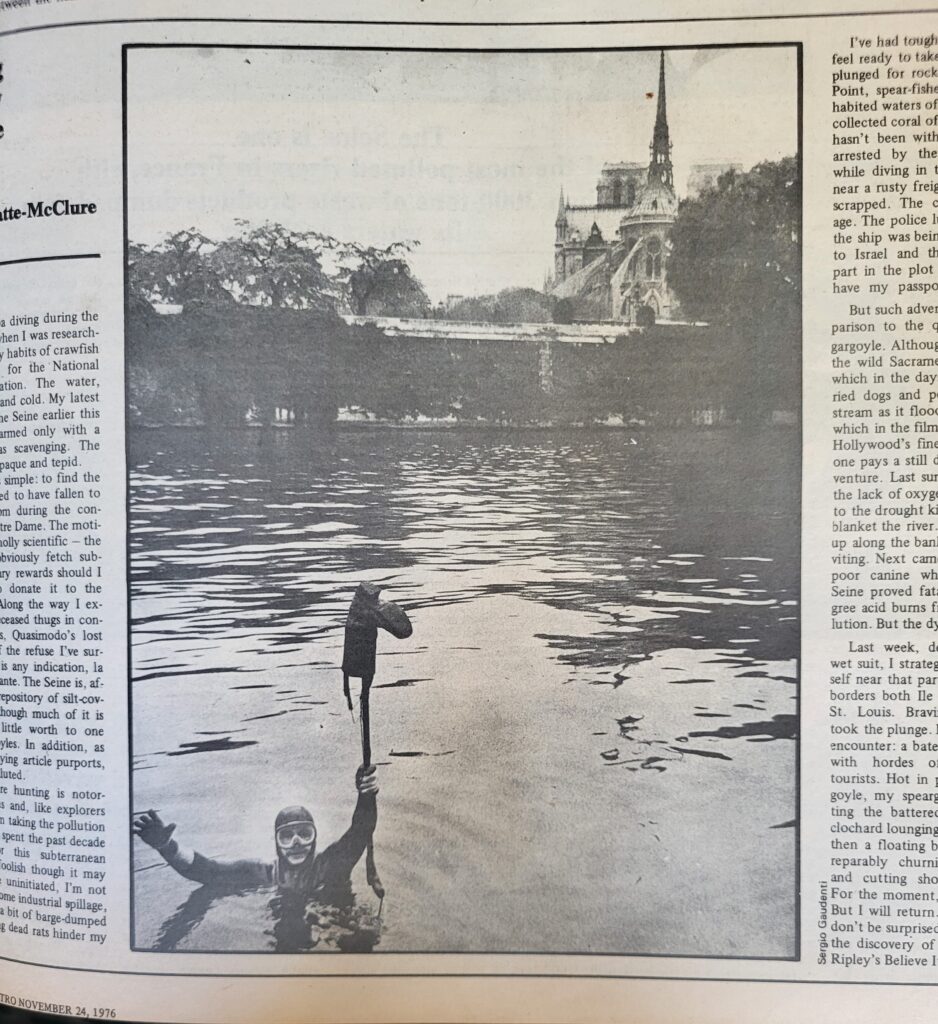

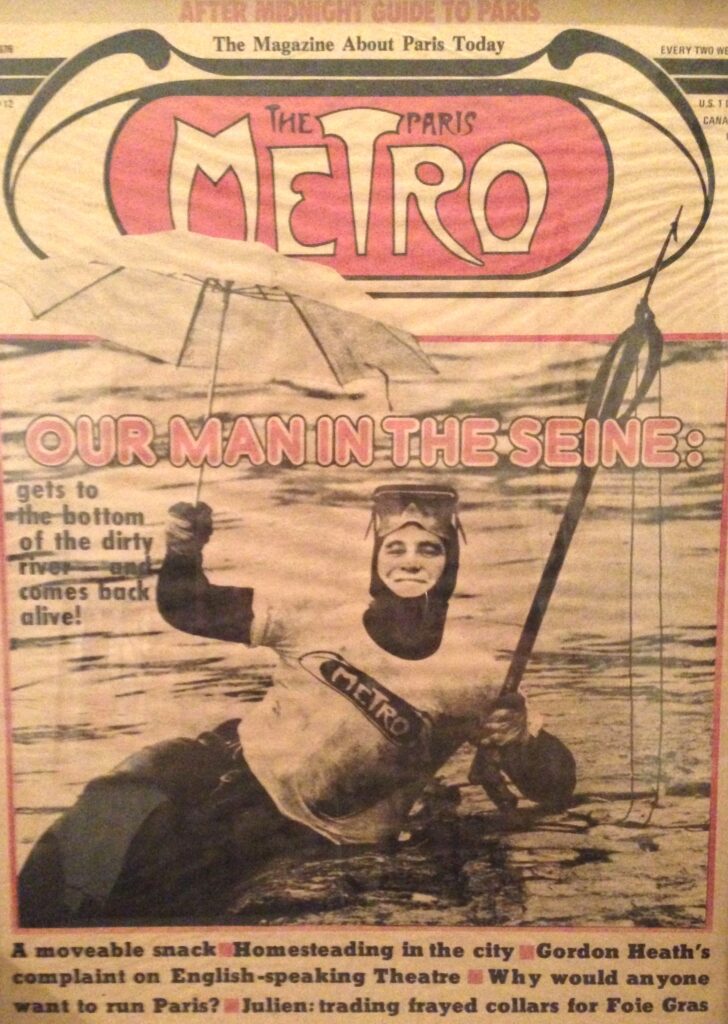

The waters weren’t too pristine in 1976, either, when Joel jumped in from the banks of the Île Saint Louis wearing a wet suit and carrying a spear gun. His stated goal was to find the stone gargoyle that allegedly fell into the river during the construction of Notre Dame some 800 years before. He emerged only with a man’s boot.

It was in the name of journalism. Joel was doing a story for Paris Metro, the storied Village Voice wannabe that lasted less than two years but continues to inspire nostalgic testimonials.

At the time I was a 23-year-old intern in Paris working for McGraw-Hill magazines (Joel was a colleague), and I also wrote for Metro. My stories were on rape in Paris and on the city’s first mayoral election ever (a government-appointed prefect had run things before.). In that one I failed to call the eventual winner: Jacques Chirac, who went on to occupy the post for 18 years while also serving as prime minister twice. He was later president.

I never swam in the Seine and, even if I had been tempted, there were good reasons not to. That summer, pollution in the river had killed thousands of fish, whose bodies floated on the water and stank up the air. They were mostly gone by the time Joel dove in in the fall.

Joel, whose distinguished writing career includes 20 years of walking around the Mediterranean and writing three books about it, lives in Paris part-time now. We had lunch recently in a restaurant on the Île de la Cité, near the river, and rehashed our Metro days.

Afterward we walked over to survey the Seine. The waters are running very high at the moment and they sure don’t look clean, despite a $1.5 billion investment in stormwater and sewage treatment.

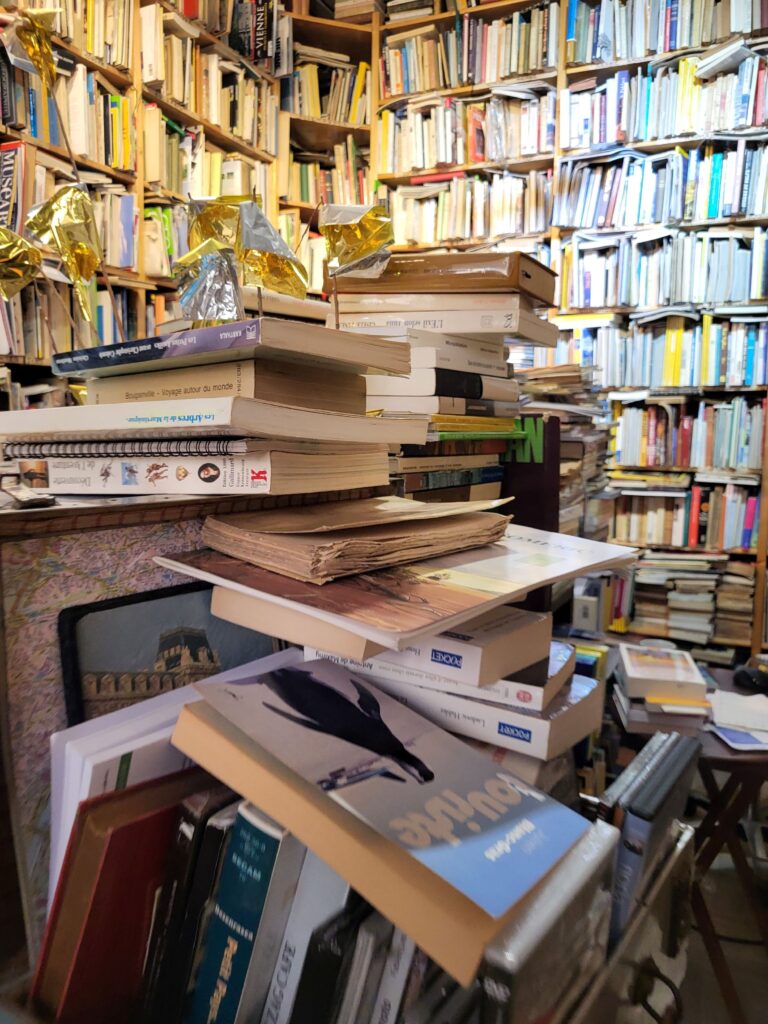

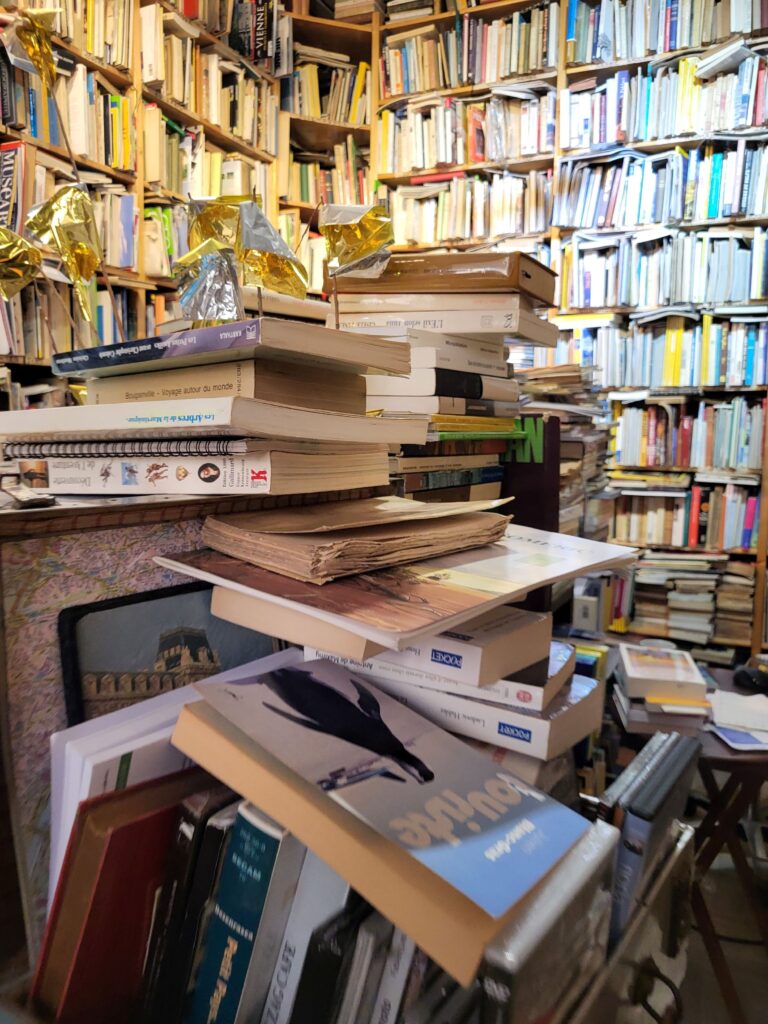

Then we decided to check out Joel’s original diving spot. On our way, we passed an unusual bookshop run by a friend of Joel’s, Catherine Domain. At 83 years old, she’s decided not to let any customers in because, a sign explains, the store only has one search engine and it’s Catherine.

She did grant us entry, because she’s known Joel for so long.

We weren’t able to walk all the way down to the place where Joel had swum 48 years ago because of the high waters, but some swans were there, and a duck. I’d never seen swans on the Seine before and wondered if they were a sign the cleanup effort was working.

Swimming in the Seine has been banned since 1923 because of pollution, bacteria and boat traffic. Before that, Elaine Sciolino writes in “The Seine: The River That Made Paris,” river dipping was big, practiced in the nude by King Henri IV in the 17th century and later by Parisians who swam in floating pools. They apparently ignored the smells and waste from dead animals, tanners’ dye and human excrement.

It’s a sad history for the waters that flow through the heart of Paris, which Elaine calls “the most romantic river in the world.”

“She encourages us to dream, to linger, to flirt or fall in love, or to at least fantasize that falling in love is possible.” — Elaine Sciolino, “The Seine, the River That Made Paris”

The Seine has been part of my life in Paris all during our decades here, especially when we lived on the rue de Lille on the Left Bank in the 7th arrondissement. Only a block from the water, the street features a plaque about three feet from the ground marking the high point of the 1910 flood.

We held Charlie’s 50th birthday party on a houseboat on the bank five minutes from our apartment, and used to have dinner parties around a bench on the Solferino footbridge nearby.

Daily enjoyment also includes the pleasure of walking, biking, busing or driving over the river. And when the rains get heavy, Parisians measure the height of potential floodwaters by how near they are to the feet of “Le Zouave,” a statue of a colonial soldier from Algeria who helps hold up the Alma bridge. It’s now around his feet; I’ve seen it almost to his waist.

Officials say the water will be clean and that there is no Plan Bexcept for delaying the triathlon and open-water events by a few days if needed. The Zouave can count on having a little company come this summer.

Follow

Follow